Historic letters found on Royal Pavilion Estate give a fascinating glimpse into the everyday lives of soldiers hospitalised on site during the First World War

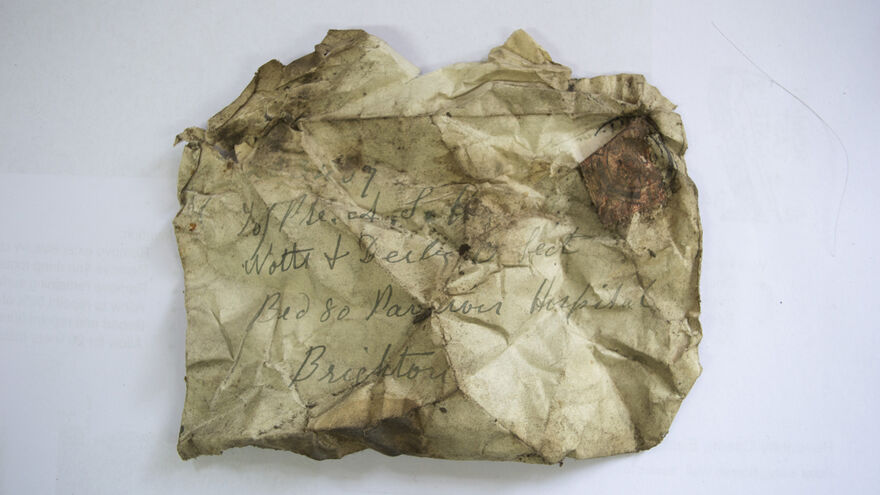

Several personal letters dating from the First World War usage of the Royal Pavilion Estate as a hospital for soldiers, have been discovered during redevelopment work at Brighton Dome Corn Exchange.

The letters, which were discovered in both whole pages and in fragments, by workers on site, give a fascinating glimpse of what life was like for the hospitalised soldiers.

One letter, dated 20 April 1918 from JC Cocks a patient at Queen Marys Hospital, Roehampton, to his friend Brown a patient at the Pavilion hospital: ‘I dare say you are expecting a letter from me as to how they are treating me at the above. Well it is not too bad here at all, it is a little out of the way, we find this especially so in bad weather as amusements are not next door to the hospital as at the pavilion. I am being fitted with a [illegible] arm (a French make) it is very light in weight and will suit my purpose very well. I don’t think this arm is suitable for manual labour & what I have seen of the arms I should think a Anderson + Whitelaws would suit you’

In another letter, a Private writes from Boulogne base: ‘Dear Fred, I hope you are much better now. I have had another turn in hospital. I fell down and grazed my eye and knee and got some fluid under the knee cap: but it has got quite alright now. I was carrying a tray of Beef and tripped over a sack of harness.’

A third letter (torn into fragments) dated 25 August 1918 was addressed to ‘My Dear May’ from a patient in ‘Section D 120, The Pavilion, Brighton’

Along with the letters, a collection of other items was found including a knife, match and cigarette packets, bottles, newspaper cuttings (including from The Times of India), sweet wrappers, a toothpaste tube, and boot polish.

Michael Shapland, Historic Building Specialist at Archaeology South East says ‘The letters came from behind the rear cladding to the timber frame of the Corn Exchange, rather than from within the timber frame. Essentially, the letters could only have got there by being dropped from above into a narrow void behind the Corn Exchange hall, rather than being inserted at ground level from within the hall itself.

The interesting thing about this context is the presence of a skylight precisely above where the letters, together with the other ephemera, would have been dropped. We can therefore begin to tell a little story here, whereby soldiers packed into the busy infirmary ward itself would have snuck off to quiet corners of the building (such as the roof-space) to have a fag and read their letters in peace, in the light provided by the skylight.’

From 1914 to 1916 the Royal Pavilion along with what is now Brighton Dome Concert Hall and Corn Exchange was used as a state of the art hospital for Indian soldiers who had been wounded on the battlefields of the Western Front. From 1916 to 1920 it was used as a hospital for British troops who had lost arms or legs in the war.