How Chrysanthemums found their way to the Royal Pavilion Gardens

To celebrate Heritage Open Days 2020 we are publishing a series of blogs researched and written by Brighton Dome's heritage volunteers. The blogs reveal the fascinating stories connecting Brighton Dome's history with the Royal Pavilion Estate and the city.

Early pictorial representations of the Royal Pavilion gardens show a romantic landscaped look, with fashionable lawns shrubs and trees, rather than flowers. It was after the time of George IV that the flower garden became popular, culminating in a positive 'frenzy' for chrysanthemums and other flowers and leading to the 'bedding' style of garden, which prevailed into the late 1800s (and still lingered long into the 20th century in displays in public parks), when a more naturalistic and relaxed style of old fashioned cottage garden became popular.

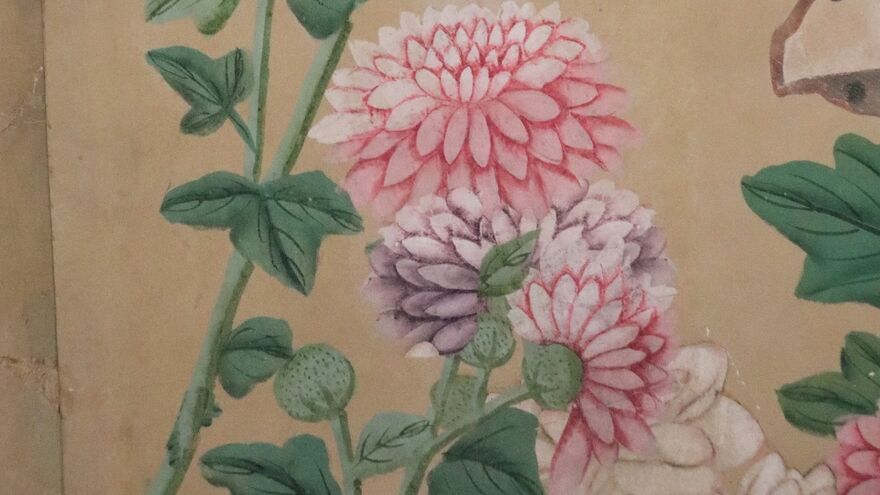

Chrysanthemums have a strong association with Eastern culture. They were first cultivated in China and pottery dating back to the 15th century BC depicts the flower as we know it today. Respect for the flower ran so deep that a Chinese city was named after it: Chie-Hsien, or Chrysanthemum City. Carvings of chrysanthemums adorned Chinese palaces and temples and an old proverb says; 'If you would be happy for life, grow chrysanthemums'. The original chrysanthemums were yellow, but botanists began cultivating and breeding different varieties before the 10th century BC.

Chrysanthemums made their way to Japan, as a gift from one Emperor to another and were just as highly revered; only nobility were allowed to grow them. It has been the national flower of Japan since the year 910 (10th century BC) and to the Japanese it represents happiness, love and truthfulness. For centuries China and Japan kept these sacred plants to themselves.

In 1771 George III invited Joseph Banks, botanist and fellow of the Royal Society, to Kew Palace, and this led to the official funding of plant hunting expeditions in England.

The royal gardens at Kew already included a physic garden and the exchange of plants had gone on between botanical gardens of Edinburgh, France, Spain, Sweden and the Netherlands, and their colonies, since the 1600s. In Sweden, Carl Linnaeus, while professor of Medicine and botany at Uppsala, sent 19 students on voyages around the world between 1745 and 1792 to bring back plants and seeds. They travelled under the auspices of the Swedish East India Company and their ships visited China, North America and the Middle East.

William Kerr, gardener at Kew, was the first professional plant hunter from England active in China. He sent back 235 plants, all new to European gardens. ‘His plants were procured in Canton and sent back to England on the ship Henry Addington in a 'greenhouse or plant cabin' prepared for that purpose'. The Horticultural Society sent other plant collectors, their aim was to obtain large numbers of living specimens and seeds to be propagated and sold to their rising number of wealthy clients. In 1823 John Damper Parks made a successful visit to China and among other things brought back 20 varieties of chrysanthemum.

After this, the political situation in China made plant collecting impossible until the 1840s, when Robert Fortune and later Earnest Wilson were able to plant hunt there again. By the time Fortune made his visit, his plants were able to benefit from the invention of the Wardian Case, an early version of the terrarium, to carry them back safely.

Written by Heritage Volunteer Alison Glasheen

Discover more heritage stories and find out more about our future.